Who reads William Burroughs? |

|

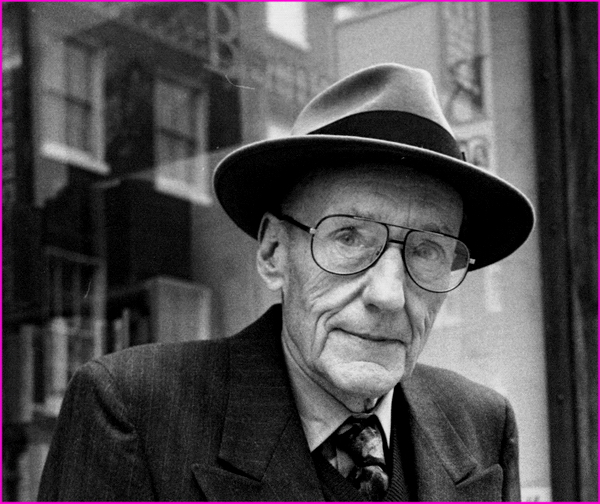

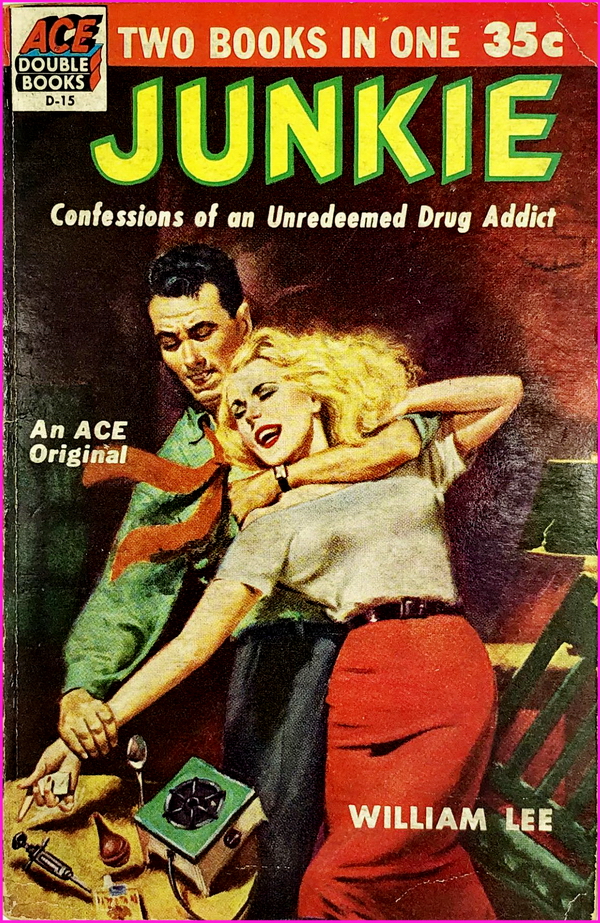

A good question. His first book Junkie was published in 1953 (under a pseudonym , William Lee) at a time when drug use was virtually unknown. The cover of the book luridly depicts an addict shooting up a vein in the forearm. It has the aura of a dime store novel, instantly disposable. For Burroughs it was his catharsis; he later claimed he ‘wrote his way out of addiction’. When The Naked Lunch was first published in 1959 Burroughs was already well known to a small circle of artists, bohemians and beatniks. These were his early readers and in a short time the book caused notoriety with the inevitable charges of ‘obscenity’ being levelled against the author. This wasn’t surprising. After all, the United States were caught in the grip of The Cold War so any literature that was perceived as being undermining of The American Spirit was easily condemned as ‘unpatriotic’, ‘subversive’ and ‘un –American’. The atmosphere was hardly sympathetic for a novel as sensational as The Naked Lunch in Europe which was still emerging from the aftermath of World War II. The drab, cold and grey 1950s and early 60s were not ready for William’s swashbuckling style of text which appeared to transgress most of the rules concerned with writing let alone the contents of the book which would no doubt have outraged the casual reader with its graphic depictions of sexual excess, random violence, sinister agencies of control and manipulation and so on. In 1961 the first book in the trilogy of cut-up novels was published. This was The Soft Machine, followed by The Ticket That Exploded in 1962 and Nova Express in 1964. All three books overlap and could be seen as one book. They are some of his most difficult works probably because the cut-up technique he so feverishly adopted is evident throughout the trilogy. What also comes through is the theme of resistance to agencies of control (church, state, and police). This theme would crop up regularly in his later books. The 1960s were good to William although I doubt if he saw it that way. Most publishers wouldn’t touch his work and so a consequence of this is the plethora of obscure journals willing to run articles and short pieces or extracts of work in progress from that era. Of course, the climate for such experimental writing had arrived. Indeed, some would say that Burroughs and the Beat literature – Ginsberg and Kerouac being the main players – set the scene for the blossoming of what became known as the counter-culture. Thus the beatniks of the 1950s paved the way for the hippies of the 1960s. |

|

Although Burroughs had little time for ‘the flower children’- (he once said the only way to give a policeman a flower was in a flowerpot from above!) they warmed to him mainly through exposure to regular articles he wrote for ‘underground’ papers like International Times (IT) from London and the Los Angeles Free Press. He lived in London during the late 60s, in fact until 1974, so his contributions to IT and other main London underground paper, Friends (later Frendz), were not so surprising. He wrote later that he disliked London and England generally what with its archaic licensing laws (‘time gentlemen please’ is an often used phrase through many of his novels) and stuffy, class ridden institutions. Thus in July ’74 he relocated to the States, to the city he left for Tangiers back in the 50s, New York. New York at this time was on the brink of spawning another strong cultural impulse that encouraged the nascent punk scene in London. The Ramones, Patti Smith, Talking Heads, Warhol, and Television were the major influences in 1975/76 on what would eventually become punk. The punks soon recognised their spiritual godfather in Burroughs and he befriended the likes of Warhol and Patti Smith. His long time friend and former lover Allen Ginsburg encouraged Burroughs to read selections of his works to audiences around the country. And so began a series of readings at various U.S. universities and institutes. The results are captured on the excellent 4CD set released in the late 90s. His audience had expanded steadily through the 70s and 80s in part due to the readings but perhaps mainly due to his trilogy that began with Cities of the Red Night (which many feel is his tour de force), continued in The Place of Dead Roads and ended somewhat anti-climatically with The Western Lands. Despite this he was never really accepted by the mainstream but his shadow over art, music, film and literature is huge. I would contend that his contribution as a ‘reporter’ of the human situation in the latter half of the 20th century is unique and the shock waves from ‘the front’ are only now able to be assimilated and understood by the sensational, spectacular tumult that is/will be century 21.

Mush O’Rune - August 2002 |